[ad_1]

A technician works in a top-level biosecurity laboratory in Berlin that is rated to handle the riskiest of pathogens.Credit: Markus Heine/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty

As US policymakers spar over how to regulate research involving potentially harmful pathogens, a report finds that it will be difficult to do so without compromising studies that are necessary for creating vaccines and life-saving therapies.

The shifting sands of ‘gain-of-function’ research

Researchers at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology in Washington DC scanned the scientific literature using an artificial-intelligence tool to assess where and how often ‘gain of function’ (GOF) studies are conducted. These studies, in which scientists bestow new abilities on pathogens by, for instance, inserting a fluorescent gene or making them more transmissible, are common in microbiology research, the team found, but only a small fraction of the research involves agents dangerous enough to require the strictest biosafety precautions in laboratories. The researchers also found that about one-quarter of studies involving GOF or loss of function (LOF) — in which pathogens are weakened or lose capabilities — are related to vaccine development or testing.

“I was so relieved to see a data-driven approach” to assessing GOF research, says Felicia Goodrum, a virologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. It helps to support the argument that GOF studies are paramount in molecular virology and are necessary to study the impact of genetic mutations that pathogens acquire in nature through evolution, she says.

Surveying the landscape

The bitter debate over the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic has intensified calls to clarify and tighten oversight of this research. Many virologists say that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus probably spread to humans through contact with infected animals, but some argue that it could have escaped from a laboratory in which researchers might have been conducting GOF work.

This has led to intense politicization over precisely what constitutes GOF research and how it should be regulated, says Anna Puglisi, a biotechnologist and policy specialist at Georgetown, who co-authored the report. That’s why she and her colleagues produced their report: “There’s so much discussion and hype about gain-of-function research, but what does it really look like?” she asks. Getting an answer to that question is “the only way you can start to understand what the true risk for both not regulating it and over-regulating is”, she adds.

Schuerger, C. et al. “Understanding the Global Gain-of-Function Research Landscape” (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, August 2023).

Puglisi and her colleagues first identified about 159,000 original English-language research papers involving pathogens that were published between 2000 and mid-2022. They then developed a machine-learning model that looked for key terms that would identify papers containing GOF and LOF work. (The authors searched for both types of paper because microbiologists use similar experimental techniques in each case, so future regulations might affect both areas of research, they say.)

The model found about 7,000 studies that fitted the bill. The researchers then randomly chose 1,000 of those and manually sorted through them to ensure that they were, in fact, GOF or LOF studies. This left them with 488 publications.

When the authors drilled down into these, they found that about one-quarter of the studies involved only GOF work, and about three-quarters involved less controversial LOF work, either alone or in combination with GOF.

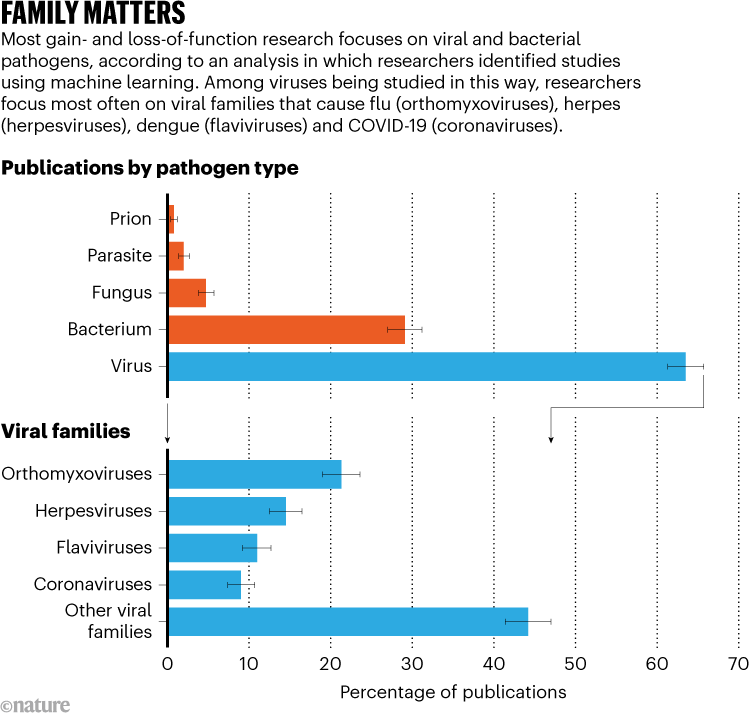

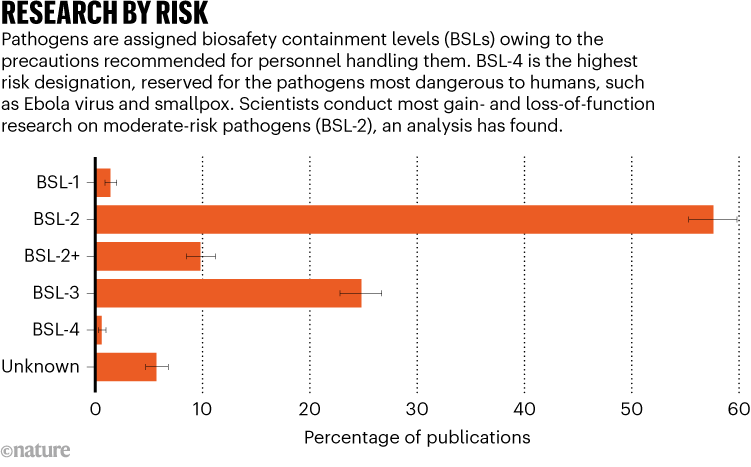

The team also explored which pathogens are studied most often, and how dangerous they are to humans. More than 60% of the research that was analysed involved viruses, and more than half of these belonged to the viral families that cause flu, herpes, dengue and COVID-19 (see ‘Family matters’). Most of the pathogens studied were of moderate risk to humans. Only 1% of the studies focused on a tier of pathogens that require the highest biosafety-containment-level precautions (BSL-4); among these are the Ebola virus and smallpox (see ‘Research by risk’).

Schuerger, C. et al. “Understanding the Global Gain-of-Function Research Landscape” (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, August 2023).

One drawback of the report, says Kevin McConway, an emeritus statistician at the Open University in Milton Keynes, UK, is that the 1,000 publications randomly reviewed by the Georgetown team might not be representative of all LOF and GOF studies. The machine-learning model might have missed studies that differ in some systematic way from those reviewed by the researchers, and that could skew the analysis, he says. Caroline Schuerger, a biotechnology and policy specialist at Georgetown who co-authored the report, responds that the findings are just the “tip of the iceberg”, and that the team’s aim was to provide the “first broad, large-scale analysis” of the research landscape.

A struggle over guidelines

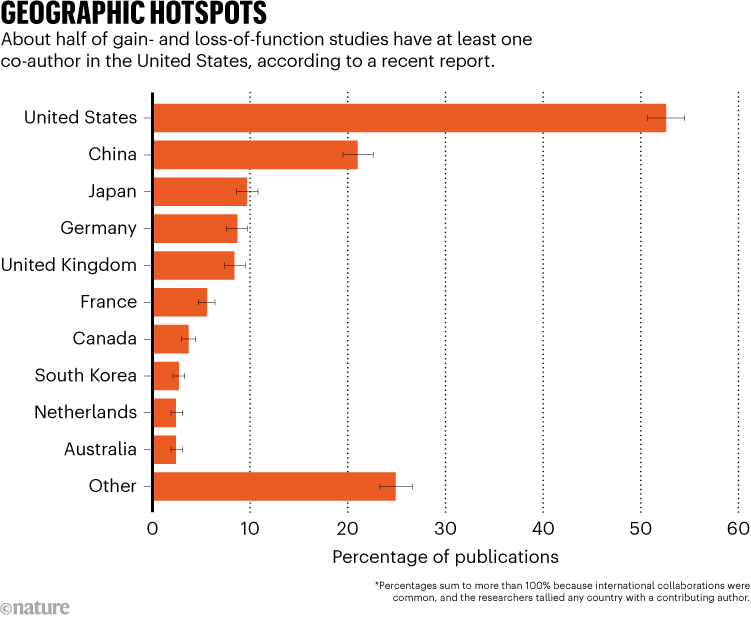

The report finds that the lion’s share of GOF and LOF research is conducted by researchers in the United States (see ‘Geographic hotspots’). This is where some of the most intense scrutiny of the work is taking place. There has been a years-long effort by US policymakers to revise the guidelines for funding and overseeing a small subset of GOF research, which aims to enhance the transmissibility or virulence of pathogens that could cause a pandemic. In January, a panel of US experts recommended broadening the criteria that funders and institutions use to determine whether proposed studies should receive extra scrutiny by health officials.

Schuerger, C. et al. “Understanding the Global Gain-of-Function Research Landscape” (Center for Security and Emerging Technology, August 2023).

But some lawmakers are calling for even stronger action; legislators in Florida banned all GOF research on potential pandemic pathogens in May, and similar legislation is pending in Wisconsin and Texas. At least one bill introduced in the US House of Representatives seeks to ban the National Institutes of Health, the largest public funder of biomedical research in the world, from financially supporting any GOF research, regardless of its potential threat to human health.

Such blanket regulations are too blunt an instrument, Puglisi and her co-authors say. “One-size-fits-all policies aimed at mitigating dangers from one approach could limit other, less-risky research, and overly broad regulations could ultimately limit the scientific community’s ability to prepare for future disease outbreaks,” their report concludes.

Although the report makes this argument nicely, says Gigi Gronvall, a biosecurity specialist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, it’s unlikely that it will change many minds. The report doesn’t “get to the heart of what makes people so upset about these issues”, she says — adding that, for many, “it’s about whether we should go against nature [by manipulating pathogens] to try to determine whether something is likely to become a pandemic threat.”

[ad_2]

Source link